For the second year, I’ll be taking part in Fun a Day. This is a project where participants do something creative during January, either one project per day or something larger over the entire month.

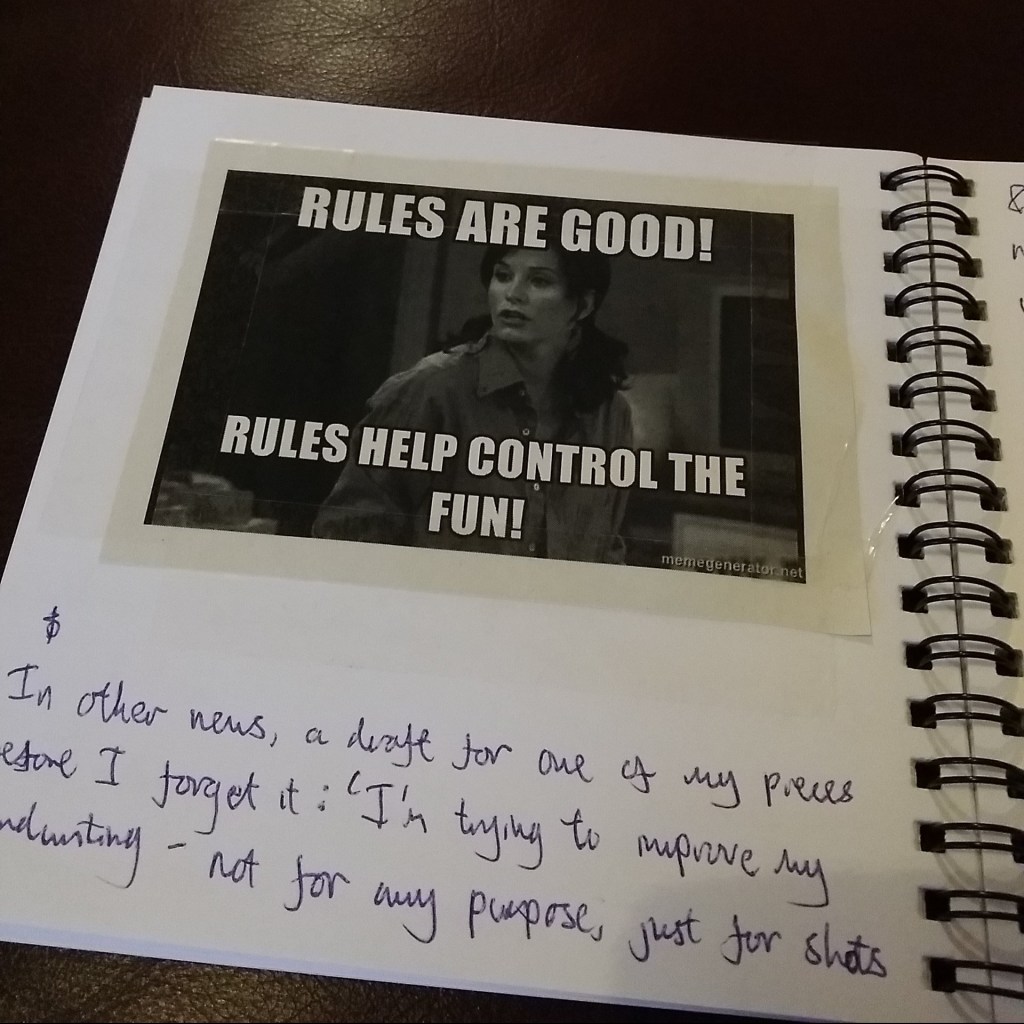

I’ve already started to document my progress in a commonplace book. With the official hashtag now announced, I posted my first two pictures online. The first contained the three rules of my project. The second contained this quote from Monica Geller in Friends.

My main project will be text-based. I’ll be writing a fragment of 40 words on Day 1, 39 words on Day 2, and so on until I’m writing 10 words on Day 31. The text will form a complete circle so the fragment on the last day will join up with the fragment on the first.

That said, being around visual artists has had an effect on me. Last year’s project consisted largely of pen on lined paper, which looked somewhat out of place compared to the other participants’ installations. Poets think about how their work looks on the page; artists think about how it looks on the wall.

In fact, the proposed title is Line for a Walk, derived from a quote by the artist Paul Klee. Depending upon which source you read, he said, ‘A line is simply a dot going for a walk,’ or ‘A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.’ I actually used this analogy to explain to the organiser what it’s like to write a novel in a month, and the phrase stuck with me.

There are side projects planned alongside the main one, but these aren’t quite so rigorously defined yet. Even if they don’t happen, January will not be a dull month.