One of the best ways to proofread a new piece is to leave it aside for a while, and then revisit it in the future. Writing and reading are two distinct processes, much like cooking and eating,

My preferred formula is to leave one minute per word, or 24 hours, whichever is longer. To find this, divide the number of words in a piece by 60. So a 600-word short story would be set aside for 24 hours, while an 80,000-word novella would be left for over 1,333 hours or around 56 days.

But what if you have a deadline that won’t allow the piece to be set aside for long? Here are three ways I’ve learned over the years to speed up the process.

Change the typeface

Microsoft Word is usually set up to type in Arial or Times New Roman, with equivalent typefaces available for Mac. However, there are countless others pre-installed on both operating systems. Save your work, then convert the text to something completely different.

I suggest picking wider letters than usual and increasing the font size, because the eye tends to focus on different parts of the same words, and any errors will seem more obvious.

Read it aloud

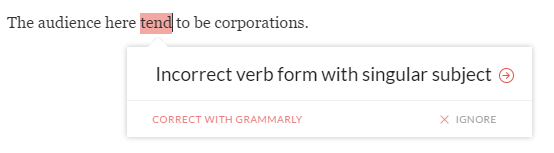

For the avoidance of doubt, there’s no need to read it to anyone, just as long as it’s out loud to yourself. This method is good for picking up poor grammar and clumsy sentence construction that reading alone often misses.

Make your computer read it out

I used to use Dragon NaturallySpeaking a lot, and that has a feature to read text from the page, although Word and other word processors also have this built in. I have a particular problem with typing form when I mean from, and vice-versa, and this method is particularly good at finding these.

Older speech synthesis is a little grating for longer pieces, but the inflections have become much more realistic over the last decade. Just ask the actor Val Kilmer, who was given a cutting-edge system after he lost his voice.

… and a disclaimer

Murphy’s Law dictates that a blog entry about proofreading will contain some errors that can’t be attributed to stylistic choices. I haven’t found any, but I’m sure my many readers will be all over it.