A couple of weeks ago, I received two copies of Is There a Book in You? by Alison Baverstock through the post. However, I have no memory or record of ordering them. They were professionally packaged in a grey polythene envelope with a printed address, but had no other identifying features.

Did you send me these books, or do you know who did? None of my friends have claimed responsibility, even the ones who are liable to such jolly japes.

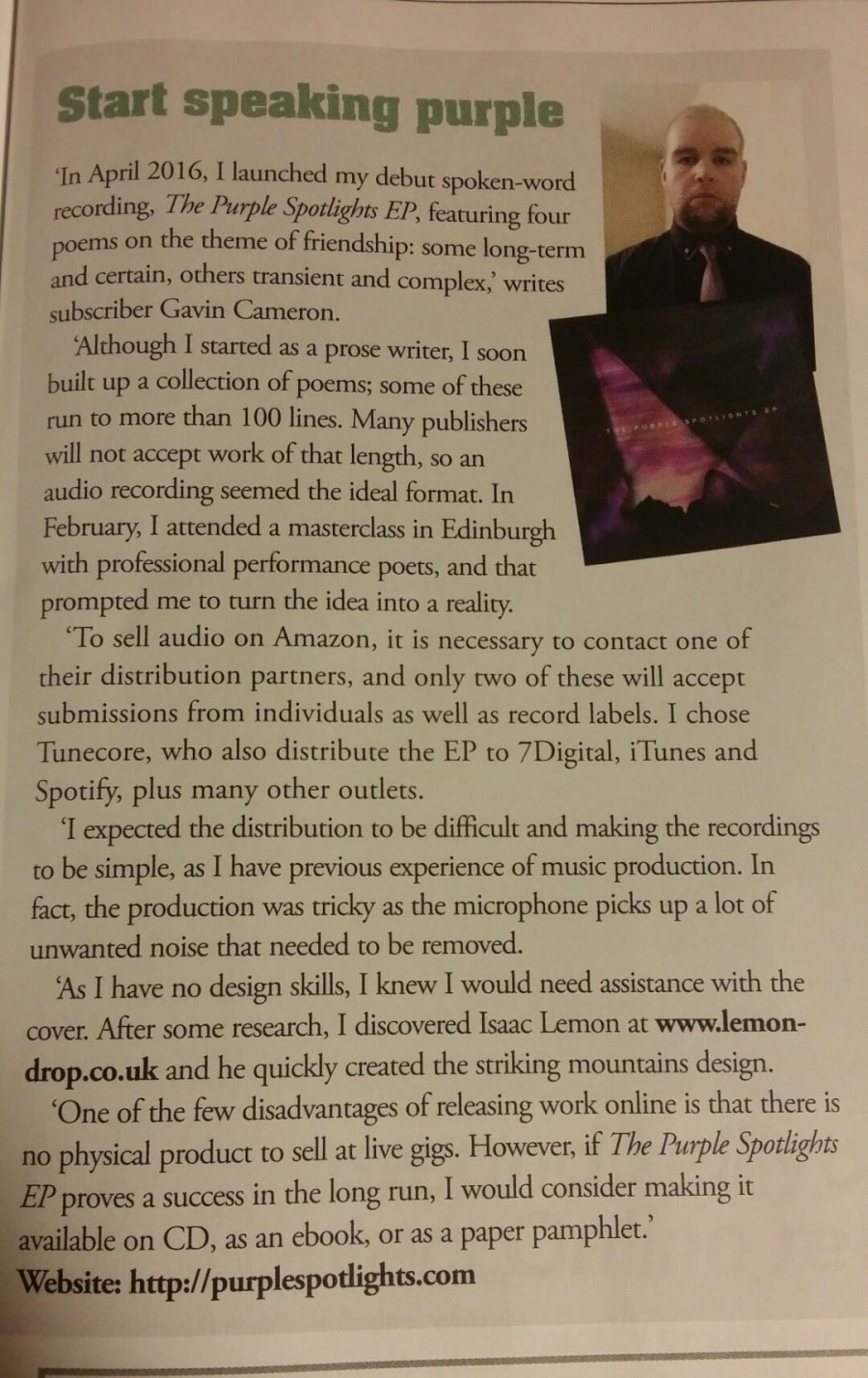

There is one possible explanation. I’m a subscriber to Writing Magazine, and I ordered two extra copies of the September edition because it featured my release The Purple Spotlights EP. Perhaps whoever put the order through accidentally marked it as a new subscription and it triggered off a welcome gift. If it is, they’re not getting them back, because it’s a lovely surprise, and when I’m ready to edit my novel again, I’ll be sure to dip in.

This year alone, I’ve really enjoyed books I’ve been lent by friends. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro was a prime example, and the similar The Girl with All the Gifts by M R Carey. I would group these two books thematically with the P D James classic The Children of Men, although I bought that one for myself and didn’t find it quite as entertaining as the other two.

The Girl with All the Gifts has now been turned into a film, and I’m curious to see how well it’s been done. Ditto the Paula Hawkins novel The Girl on the Train.

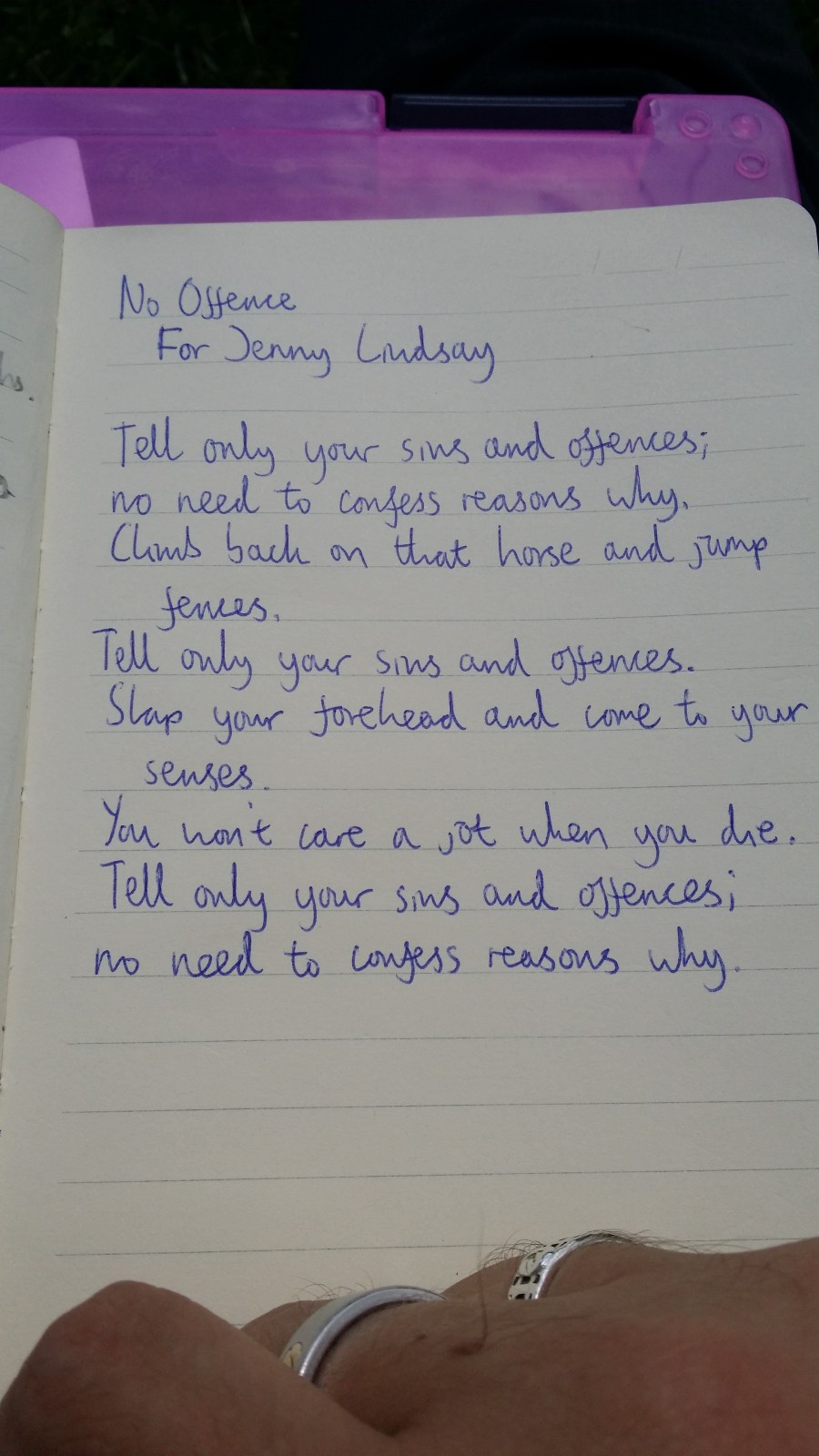

Poetry-wise, it’s been a strong year of lending as well. I was given Tonguit by Harry Giles and What They Say About You by Eddie Gibbons. The former collection gave me lots to chew upon, especially in the poems Piercings and Your Strengths; the latter volume had me laughing right past the poems to the endnotes.

Word-of-mouth is always a strong marketing tool. The people who recommended all these books are good friends, and by extension, I trust what they recommend. By and large, this trust is well placed.

In fact, there has been only one recommended book where I didn’t enjoy it: The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion. The main character is Don Tillman, a professor with autism, and that’s shown extremely well through the narrative. However, he’s at the peak of his career with a packed schedule that’s timed to the minute, so I felt he lacked a strong motivation for wanting to find a partner. There was a time I would have persisted with a disappointing book, but I stopped reading at page 41.

That said, I’m a strong believer that people should make up their own minds about which books they like and don’t like. Plenty of people love the novel, but it’s not for me. By the way, that referral came from my boss, so you can’t tell anyone I’ve admitted all this.