I’m part of the Wyvern Poets group in Dundee, having been a founder member in or around 2015.

Unlike my other groups, this one does not actively recruit members but it does publish its work. Most notably, Dundee University has invited us to put together a pamphlet for the Being Human festival every November, and to perform our work on campus.

For the rest of the year, the members each write a poem ahead of our monthly meetings. There is always an optional prompt; normally a single word like ‘environment’, ‘pace’ or ‘journey’. The poems are then discussed on a peer-review basis and suggestions are made between members.

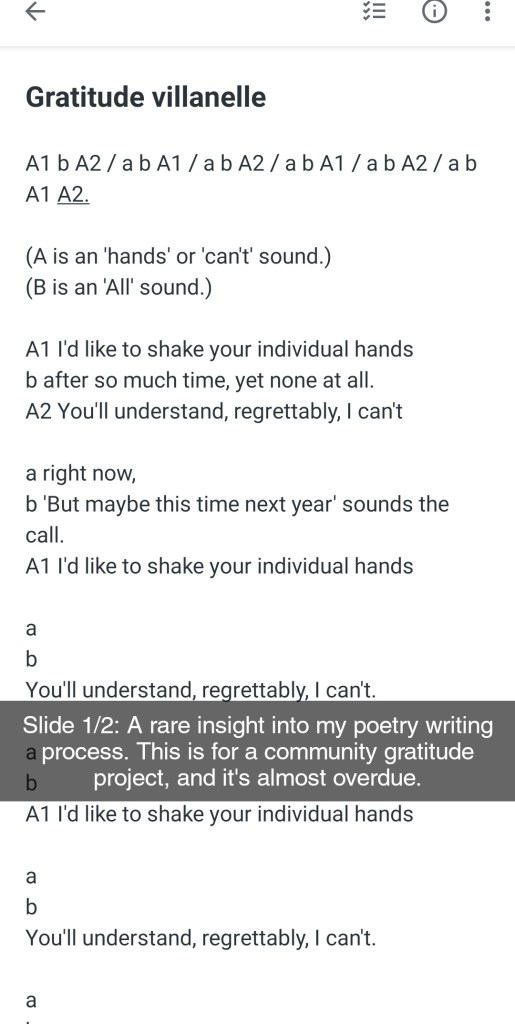

I find if I undertake no other writing in a given month, I always submit something for the group, even if it’s at the last minute or if I’m not entirely happy with it. As there’s only around a week until the next meeting, I’m going to crack on with this month’s prompt – villanelle – right after I finish this.