Regular readers will know that a few months ago, I wrote a letter to Kazuo Ishiguro after reading his book Never Let Me Go. I did it because his publisher didn’t provide anything but a postal address for its authors.

To date, Ishiguro has not replied, but I was itching to repeat the experiment with others I admire. It’s a slower and more laborious process that makes you think about every word you write. Yet the sealed envelope is far more difficult to ignore, and your words don’t become just another comment on another social media page.

With this in mind, I’ve tried to emulate the pre-Internet and pre-fax era as much as possible, a time when celebrities felt more removed from their audiences. I’m lucky enough to have mutual friends with a few popular performance poets who influence me. I’ve excluded them because they feel too ‘close’, even though we don’t know each other directly.

There’s one important concession to the old-school vibe: it would create a lot of hassle to find out the postal address of agents, management companies or publishers in an offline manner. I therefore set a rule that I was allowed to use the Web for the task, but I wasn’t permitted to contact anyone to ask for the correct details. I instead used the most likely addresses I could find.

So who are the top 10? I’ve listed them in no special order:

- Andrea Gibson – performance poet

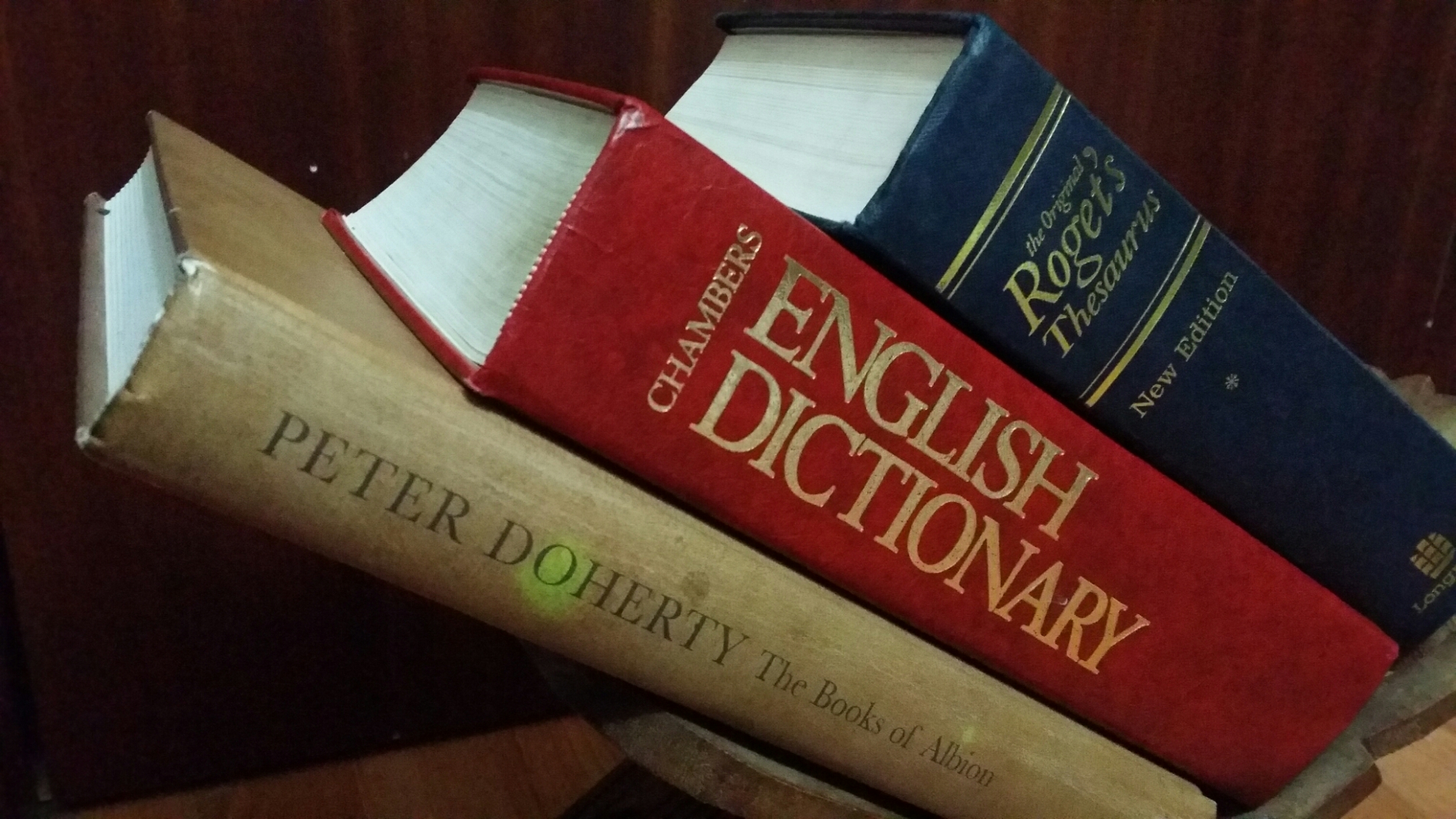

- Peter Doherty – musician and poet

- Marshall Mathers – rapper, aka Eminem

- Mike Skinner – rapper

- David Nicholls – novelist

- Tracey Thorn – musician in Everything but the Girl

- Jasper Carrott – comedian

- Billy Joel – musician

- & 10. Harley Alexander-Sule & Jordan Stephens – musicians in Rizzle Kicks

It took under an hour to collate most of the addresses. However, I counted six contacts for Marshall Mathers alone as he has a number of specialist managers, so I settled for writing to his agent. Conversely, Peter Doherty proved über-difficult to pin down. My initial searches pulled up a management company in the West of Scotland; later searches provided a much more likely address.

But finding the contact details was only the start. Before I uncapped my Biro, there were other issues I wanted to iron out.

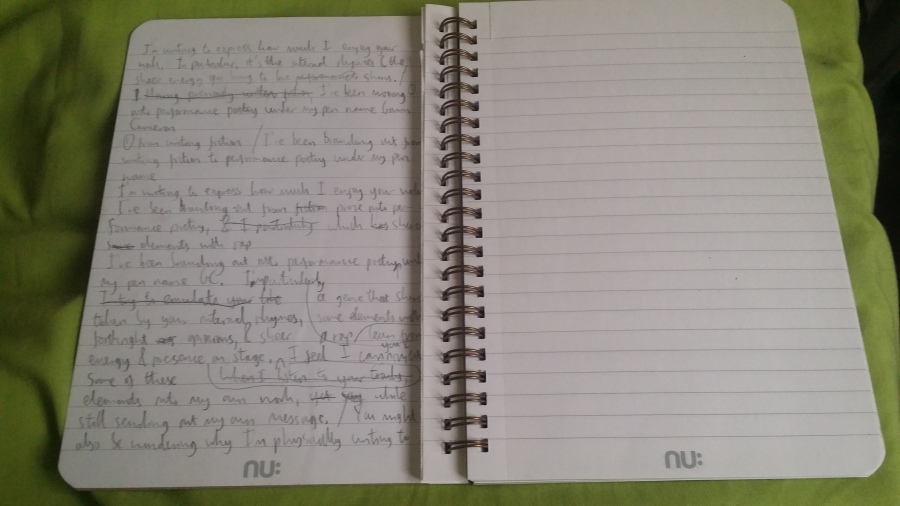

So how did I feel when I put pen to paper? I knew I would have to develop a template of sorts as it’s far easier than starting from a blank page. I first drafted the Marshall Mathers letter (pictured), then copied it onto writing paper in pen. Even with my preparations, I found it difficult at first to place my thoughts in a flowing order.

Probably the easiest letter to write was that to Andrea Gibson, which ran to three A5 pages with my signature on the fourth. I found once I’d started that I had loads I wanted to say, and I acknowledged at the end that if I’d been using a PC, I would have edited much of the ramble. I could have started a new letter, but I felt it wouldn’t have been so candid as it was in that first form.

If I did make a mistake in a word, I would simply cross it out and write it again. It didn’t occur to me until I’d sealed the envelopes that Tippex still exists. I’m glad I didn’t realise this, though, as it wouldn’t have looked pretty on the cream page.

The hardest letters were probably those to Jasper Carrott and Billy Joel. I imagine it’s because they influenced me more in my childhood than they currently do. But I’m glad I still wrote to them because I might not repeat this experiment, and none of us will be around forever.

The one thing I didn’t find intimidating at all was the level of fame my recipients enjoy. I’m currently taking the MLitt course at the University of Dundee. There, I was introduced to the concept of thinking about where I fit in with other writers and poets, including those who are well-known. So rather than considering yourself to be lower down the food chain, you’re encouraged to ponder whether you’re producing your own work to an equal standard, and how you can raise your standard if you’re not. Or in Internet jargon, MIND=BLOWN.

Thinking in those terms helped to relieve the pressure. I know I can produce work to the same standard of some of the folks I’ve contacted, and I also know I can pick holes in their work just as much as they could potentially rip mine apart. So in that respect, I’m a person doing one creative activity who’s writing to a person who does another creative activity, not a ‘civilian’ writing to a ‘celebrity’.

If I receive no replies, I won’t cry into my notebook, as I’ve said what I have to say. I’ll be happy if I attract one response; I’ll be ecstatic if I receive two; goodness knows what I’ll be like if three or more come back.

Now all I need to do is what writers do best: wait.