Last week’s entry was all about postcards. In writing about these, however, it was necessary to touch upon its replacement technology: SMS. I realised I had more to write on the matter. so today’s entry effectively serves as a part 2.

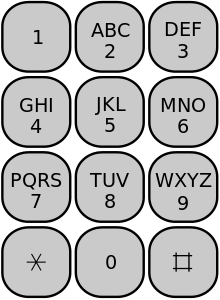

When the first SMS-capable handsets became available, they wouldn’t contain a full keyboard. Instead, each letter was mapped to the number pad in the following semi-standardised formation:

I say ‘semi-standardised’. The 0 key usually acted as spacebar, while 1 often produced symbols, but some layouts deviated from this. Ditto the toggling of capital letters, which we’ll disregard for the following demonstration.

To type the word BOOK, the following steps were necessary:

- B required two presses of 2.

- O – three presses of 6.

- Pause for a second or press the right arrow, depending on phone, to allow the letter to register. O would otherwise loop back around to M.

- O – three further presses of 6.

- K – two presses of 5.

Overall, quite the frustrating process. It quickly became accepted practice to omit letters from words or use soundalikes. This might morph the word thanks into thx, or tomorrow into 2moro, which are still reasonably legible.

There were further innovations to come. One was the T9 system, which guessed each letter in context based on its neighbouring presses. To type the aforementioned BOOK, you would press the buttons 2-6-6-5 once each. The display might suggest BOOK first, but COOL or CONK could be selected from the menu, cutting down on overall presses.

Many phones would remember which words were used most commonly, but my Nokia 3330 never did. If I wanted to mention my pal Amy, I always had to scroll through BOX and COW.

Despite T9, the abbreviated style still persisted in popular culture for some time, with Fall Out Boy releasing a single as late as 2007 titled Thnks fr th Mmrs. It only died out when touchscreen input became more common.

Cards on the table, I was never sorry to see SMS speak disappear. Although it took longer, I liked to write my sentences out properly, and it could be challenging to decode some abbreviations. I much prefer what we have these days. No doubt the style will make a resurgence at some point, but I won’t be participating in that.